- Austausch & Vernetzung

- Wissen & Lernen

- Advocacy

- Unsere Themen

Von Patrick Durisch

The political declaration of the UN high-level meeting on NCDs lacks recognition that medicine prices are excessive and hinder universal access. But a clear reference to public health safeguards was at least included, thanks to the fight back of G77 countries and civil society writes Patrick Durisch.

Two important high level summits (HLM) are taking place in New York during the 73rd session of the UN General Assembly, on the fight to end Tuberculosis (TB, 26 September) and on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases (NCDs, 27 September). These are important opportunities to raise attention at the highest Heads of States levels and reach a strong political commitment towards major health issues.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), NCDs represent an ever-increasing health burden worldwide, with more than 40 million deaths in 2016 (71% of global mortality) – rising disproportionately among low and middle income countries (LMIC) where over three quarters of NCD deaths occur. The four main NCDs are cardiovascular diseases (44% of NCD deaths), cancer (22%), respiratory diseases (9%) and diabetes (4%). NCDs are thus a major health priority in LMIC too, not only in wealthier nations.

Prevention programmes such as tobacco control or healthier diets undoubtedly represent a very important pillar to reduce the number of NCDs on a longer term. However, the NCD community should not “become trapped in an ideology that privileges prevention over treatment – a similar mistake that disfigured the early response to AIDS ”, as one advised commentator recently wrote in The Lancet (Richard Horton, Why has global health forgotten cancer? The Lancet 2018), concerned about the absence of commitment of the international community regarding cancer treatments.

Thanks to the monopoly conferred by patents – and the resulting bargaining power leading to excessive pricing – access to newer cancer treatments has become a global issue. Cash-strapped government health programmes have started rationing treatments even in a rich nation like Switzerland due to skyrocketing medicine prices. Universal access to affordable treatments, in particular for cancer, is crucial if the international community is serious about achieving the sustainable development goals 3.4 (reducing by one third premature mortality from NCDs) and 3.8 (universal health coverage) by 2030 (UN: Sustainable Development Goal 3).

The word “price”, however, does not appear in the final political declaration on NCDs, despite serious concerns having been repeatedly raised by the G77 countries and a coalition of 242 civil society groups.

A major point of contention in both HLM political declarations was the duly referencing of public health safeguards known as TRIPS flexibilities. These are enshrined in law by the 1994 World Trade Organisation Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement and the 2001 Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health. They include compulsory licensing, a legal instrument that allows governments to authorise the manufacture of lower cost generic medicines even where patents exist in the name of public interest.

TRIPS flexibilities have long been (and continue to be) a point of political friction between countries hosting big pharmaceutical corporations – led by the US, EU, Japan and Switzerland – and the G77 countries (including BRICS countries). The first group has repeatedly tried to water down language, avoid or even drop reference to these flexibilities on several instances (WHO resolutions, UN high-level meetings and reports), wrongly arguing that their use should be limited to exceptional circumstances and do not apply for cancer and other NCDs. In its Health Foreign Policy, Switzerland states for example that “the application of TRIPS flexibilities in emergency situations is recognised” (Swiss Confederation, Swiss Health Foreign Policy, March 2012), failing to mention that countries are free to determine the grounds for granting compulsory licences and that their use is not at all limited to emergency situations according to the WTO (WTO 2018: Compulsory licensing of pharmaceuticals and TRIPS).

The intention of pharma-hosting countries is to leave the use of TRIPS flexibilities and the Doha declaration open to interpretation – even though a WTO panel reached the conclusion that the Doha Declaration has the status of an agreement, and is not just a mere “declaratory” re-affirmation of the right of WTO members to take measures for the protection of public health (WTO panel finds 2001 Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health is an agreement between members).

According to international law, countries have therefore a sovereign right to use TRIPS flexibilities to the full whenever they deem it necessary for their own domestic purpose. However, this right is regularly been contested by countries hosting big pharmaceutical corporations such as Switzerland, going as far as putting undue diplomatic pressure whenever LMIC intend to use TRIPS flexibilities.

For Switzerland, this results in a schizophrenic attitude between, on the one hand, general wholehearted statements in favour of universal access to life-saving NCDs treatments and, on the other hand, the protection of their domestic economic interests. Cancer drugs represent indeed a very lucrative business for the Swiss pharmaceutical companies Roche and Novartis, which count among the global leaders in the oncology sector. This schizophrenic attitude of the Swiss authorities has come again to the forefront during Public Eye’s recent campaign for affordable medicines.

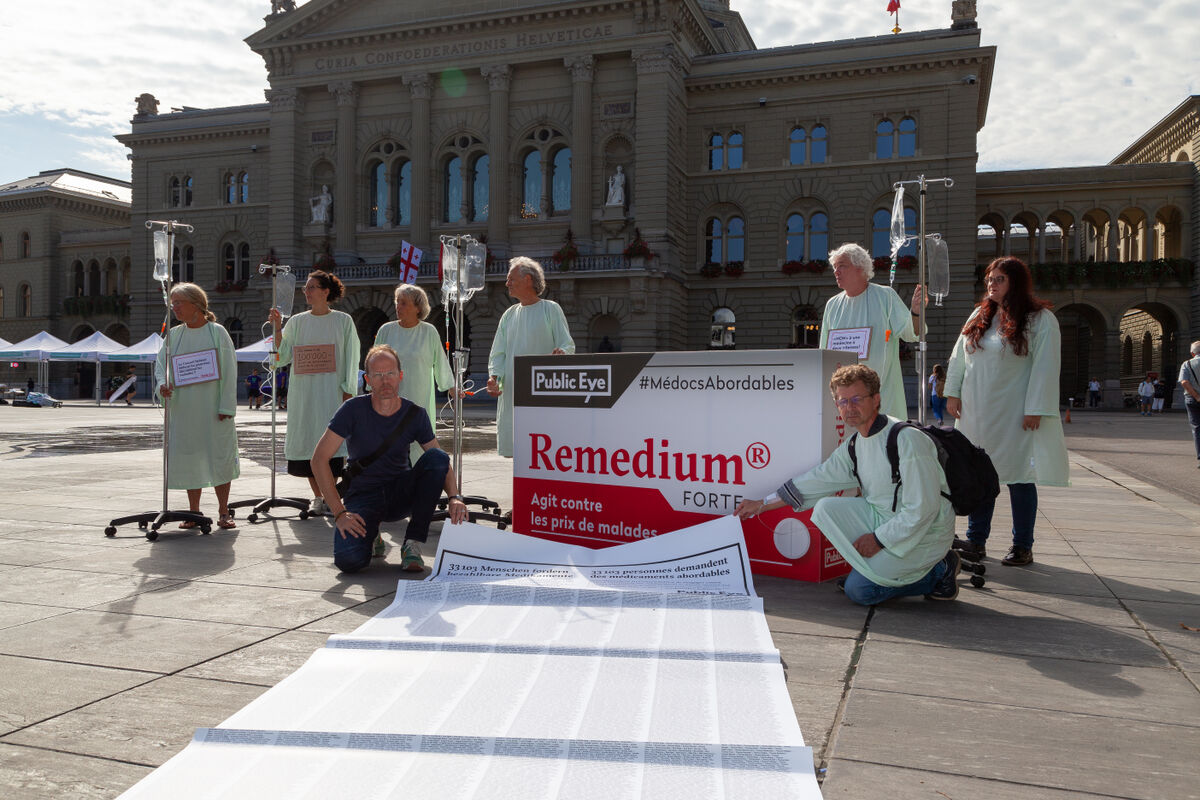

Over 33,000 concerned citizens signed the collective petition launched by Public Eye calling on the Swiss government to make use of compulsory licensing whenever the defence of the public interest requires it – that is to say, when access to all is jeopardised by rationing decisions (which is already the case) and/or when the sustainability of the healthcare system is at stake. Medicines already represent well over 20% of the Swiss mandatory health insurance scheme expenses, and the cost of oncology drugs in our country rose by 184% from 2007 to 2016 due to ever-increasing prices, frequently beyond the bar of 100’000 Swiss francs per patient per year. A new treatment launched by Novartis in the USA (and soon in Europe and Switzerland) is priced at nearly half a million dollar for a single injection, indicating that this inflating trend is not going to revert soon, quite the opposite.

The current price control mechanism is toothless with regards to patented drugs that enjoy a monopoly situation, and governments are forced to accept tremendously high price tags that have no proven correlation with actual research and development costs. Yet solutions do exist to mitigate the adverse effects of patent-related monopolies: compulsory licensing. As this TRIPS flexibility supposedly threatens the financial interests of pharmaceutical firms, the Swiss government is however trying to use any diversionary argument or tactic for not recognising it, let alone using it, despite its proven track record regarding affordable access to life-saving medicines.

The reactions of the Federal Council to recent parliamentary interventions on the subject are in stark contrast with what actually happens on the ground. Whilst the government claims it recognises the sovereign rights of other countries to use TRIPS flexibilities (Response of the Federal Council to a parliamentary intervention by MP Arslan Sibel, 29 August 2018) Switzerland intervened and exerted undue diplomatic pressure whenever Colombia announced its wish to contemplate a compulsory licence on a Novartis drug (Public Eye, Glivec en Colombie : les autorités suisses volent au secours de Novartis, press release, 2015) – or is simultaneously pushing for provisions that will hamper the use of these TRIPS flexibilities in a free trade agreement currently being negotiated with Indonesia (Open letter of Swiss and Norwegians civil society groups to EFTA Ministers of Trade, 11 September 2018). Whilst the government expresses its concern over “excessive medicine prices” and acknowledges that “additional measures (than the existing price control mechanism) are needed to curb the price inflation that puts a high burden on the social security system”, it claims that “compulsory licensing is not an appropriate tool to reduce patented medicine prices” and that “it is not entitled to act” – ignoring the instrument of public non-commercial use licence (more commonly called “government-use licence”) that is actually foreseen in the Swiss law (Response of the Federal Council to a parliamentary intervention by MP Angelo Barrile, 14 September 2018).

In summary, the Swiss government is conscious of the problem related to excessive cancer medicine prices, but prefers to protect patents rather than patients. Switzerland should definitely have the political courage to act in the public interest rather than merely protecting the financial interests of pharmaceutical companies should the global fight against NCDs be a real priority. In Switzerland or elsewhere, access to lifesaving medicines should not come down to a question of how much money you have.